Chiara Lubich – uma forma de se pensar a pulsão de vida

13 de maio de 2020

De pandemia em pandemia: “Uma pandemia de psicologia-pop”…

25 de maio de 2020Fausto Antonio de Azevedo

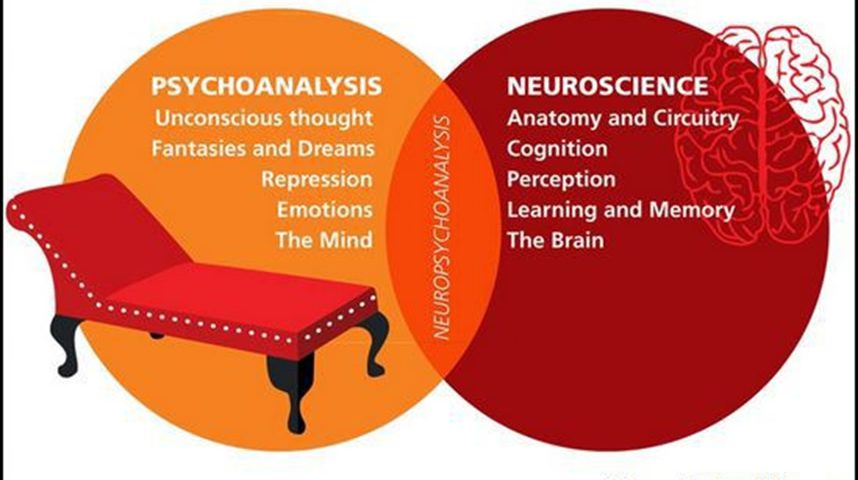

O psicanalista e neurocientista sul-africano Mark Solms, nascido na Namíbia em 17/julho/1961 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Solms; https://pt-br.facebook.com/drmarksolms/; ver suas publicações em https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mark_Solms2), tem trabalhado demais com pesquisas de neurociências e, também, com a psicanálise freudiana e os elos entre ambas. Autor de inúmeros artigos, capítulos e livros (por exemplo, seu segundo livro, “The Neuropsychology of Dreams”, 1997, trouxe uma contribuição respeitável para tal área; “The Brain and the Inner World”, 2002, com Oliver Turnbull, tornou-se um best-seller, sendo traduzido para 13 idiomas; destaque-se ainda “A Moment of Transition: Two Neuroscientific Articles by Sigmund Freud”, 2019, com Michael Saling), Solms nos apresenta, resumidamente, uma explicação clara do processo psicanalítico empregando termos contemporâneos e associando a psicanálise aos recentes achados das neurociências. Para os psicanalistas pode haver um importante ganho terapêutico com as descobertas e reflexões deste autor. Vejamos uma lista de 22 considerações suas, ao mesmo tento esclarecedoras e bastante provocantes; algo dosado de forma instigante para acalorar as discussões e motivar novas pesquisas…

- “Mental states are not reducible to brain states, or vice-versa. Psychoanalysis and neuroscience provide two observational perspectives upon the same thing. Freud called this ‘thing’ the mental apparatus, and he explicitly acknowledged that it can be studied from both points of view.”

- Freud used neuroscientific findings from his own times to construct his model of the mental apparatus. Specifically, he adopted the notion that consciousness is bound up with perception and is accordingly a functional attribute of the cerebral cortex. It is therefore legitimate to correct Freud on this score, using subsequent neuroscientific findings.

- The following two findings are most relevant in this respect:

(a) Consciousness arises from core brainstem structures that perform the functions which Freud attributed to the ‘id’. The id is therefore not unconscious.

(b) The cortical ‘ego’ is intrinsically unconscious and derives its capacity for consciousness from the brainstem id. The ego is therefore not the fount of consciousness.

- Consciousness is revealed to be a fundamentally affective function. This is not an idiosyncratic idea of my own; the same view is defended by Panksepp and Damasio (to mention only its two most prominent proponents).

- If the id is conscious, this raises an obvious question: what is ‘the unconscious’ and where is it located in the brain?

- Neuroscientific research shows that unconscious (‘non-declarative’) memory systems are located primary in the subcortical ganglia of the forebrain. It is important to note that these memory systems generate action programmes (responses), not ideas (images).

- My own view, consistent with that of Friston, is that these programmes take the form of predictions, that is, predictions as to what one can do to meet one’s drive needs. Memory is about the past but it is for the future.

- The aim of all learning is to automatize such predictions. Uncertainty and delay are the mortal enemies of predictive systems. Automatization involves a memory process called ‘consolidation’.

- Some predictions are legitimately automatized and others are illegitimately (or prematurely) automatized. The second type is called ‘the repressed’. The repressed consists in the least-bad predictions a child can muster when it is overwhelmed by insoluble problems (i.e., by unmeetable drive needs).

- Non-declarative memories cannot (by definition) be brought back to consciousness. I.e., they cannot be ‘reconsolidated’ in declarative memory. When they are activated, they are not retrieved they are enacted. Repressions can therefore never be undone through remembering.

- Our drive needs become conscious at their source as feelings (hence ‘The Conscious Id’). Legitimately automatized predictions regulate such feelings successfully by meeting the underlying need; illegitimately automatized predictions do not. That is why our patients suffer mainly from feelings. They suffer from unmet emotional needs.

- Freud conceptualized this under the heading of ‘the return of the repressed’; but the repressed itself does not return, the unregulated feeling does.

- Secondary ‘defences’ (which are not synonymous with repression) are designed to get rid of the feelings arising from the inevitable failure of repressed predictions. That is why falling ill coincides with a failure of defences.

- Neuroscientific research shows that we have far more than just two drive needs. Using Panksepp’s taxonomy, failure to meet ‘emotional’ drive needs is what most frequently gives rise to psychopathology. Bodily (‘homeostatic’ and ‘sensory’) drives are easier to master. The requisite predictions are largely reflexive and instinctual. The mastering of emotional needs – which frequently conflict with one another — requires a great deal more learning from experience (i.e., overriding and supplementing of instinctual responses).

- I believe that our clinical work is greatly enhanced if we use the unregulated feelings which our patients suffer from as the starting point of our analytic work. From conscious feelings, we can infer which underlying emotional needs are not being met. This, in turn, facilitates the identification of the repressed predictions that the patient is (unsuccessfully) using to meet that need.

- The repressed predictions are inferred from the ‘transference’. Transferences, please note, are automatized action programmes. They cannot be remembered (see above) but they are repeated; they are automatically enacted.

- Transference interpretation unfolds over four steps:

(a) ‘Can you see that you are constantly repeating this behaviour?’

(b) ‘Can you see that it is meant to meet this need?’

(c) ‘Can you see that it doesn’t work?’

(d) ‘Can you see, that is why you are suffering from this feeling?’

- Transference insights enable patients to generate new and better predictions, but these do not reconsolidate and thereby extinguish the old ones. For that reason, despite the insights patients attain from transference interpretation, they still continue to enact the old action programmes. Transference interpretations, therefore, need to be repeated until patients can make them for themselves, ideally, while the enactment is happening rather than afterwards, so they can change course (utilize a new and better prediction). This is called ‘working through’.

- It takes a long time to automatize new predictions. In cognitive neuroscience, we say that non-declarative memories are ‘hard to learn and hard to forget’. That is why psychoanalysis requires many and frequent sessions. (Those who want quicker treatments must learn how learning works.)

- The new predictions are gradually preferred over the old ones because they work; they actually meet the underlying need. But the old ones are never extinguished. That is why our patients can always return to their old ways, especially under pressure.

- The few points I have just made:

(a) bring our basic theory into line with current neuroscientific knowledge;

(b) enable us to explain the scientific rationale of our therapy to colleagues in allied fields in a way they can understand;

(c) open our theory and therapy to ongoing scientific scrutiny and improvement.

- I am mindful of the fact that neuropsychoanalysis focuses almost exclusively on elementary Freudian ideas, but we had to start somewhere. These ideas are our common ground. I am also aware that many of the points I have made here already form central tenets of some post-Freudian approaches. This is not surprising; we do what works, but now we know more about why it works.

[Fonte: https://www.therapyroute.com/article/how-to-do-psychoanalysis-by-m-solms, acessada em 20/maio/2020.]

Obras do autor em Português:

- Lynn Gamwell, Mark Solms. Da neurologia à psicanálise – desenhos neurológicos e diagramas da mente por Sigmund Freud. [Tradução: Jassanan Amoroso Dias Pastore.] São Paulo: Editora Iluminuras, 2000. 160 p.

- Karen Kaplan-Solms, Mark Solms. O que é a neuro-psicanálise: a real e difícil articulação entre a neurociência e a psicanálise. [Tradução: El. do Vale.] São Paulo: Terceira Margem. 2004.